SHURI-TE

Okinawan martial arts refers to the martial arts which originated among the indigenous people of Okinawa Island in Japan, most notably karate, tegumi, and Okinawan kobudō.Due to its central location, Okinawa is full of Japanese people and was greatly influenced by these other cultures, with a long history of trade and cultural exchange with China that greatly influenced the development of martial arts on Okinawa.The precursor of present-day Okinawan martial arts is believed to have come by way of visitors from China. In the 7th century, Chinese martial arts were introduced to Okinawa through Taoist and Buddhist monks. These styles were practiced in Okinawa and developed into Te (Hand) over several centuries.

In the 14th century, when the three kingdoms on Okinawa – (Chūzan, Hokuzan, and Nanzan) – entered into a tributary relationship with the Ming Dynasty of China, Chinese Imperial envoys and many other Chinese arrived, some of who taught Chinese Chuan Fa (Kung Fu) to the Okinawans. The Okinawans combined Chinese Chuan Fa with the existing martial art of Te to form Tōde (Tuudii T’ang hand, China hand), sometimes called Okinawa-te .

In 1429, the three kingdoms on Okinawa unified to form the Kingdom of Ryūkyū. When King Shō Shin came into power in 1477, he banned the practice of martial arts. Tō-te and kobudō continued to be taught in secret. The ban was continued in 1609 after Okinawa was invaded by the Satsuma Domain of Japan. The bans contributed to the development of kobudō, which uses common household and farming implements as weaponry.

By the 18th century, different types of Te had developed in three different villages – Shuri, Naha, and Tomari. The styles were named , Shuri-te, Naha-te and Tomari-te, respectively. Practitioners from these three villages went on to develop modern karate

Shuri-te (首里手Okinawan: Suidii) is a pre- World War ll term for a type of martial art indigenous to the area around Shuri, the old capital city of the

Ryukyu Kingdom.Shuri-Te is the name of the particular type of Okinawan martial art that developed in the Shuri, the ancient capital of Okinawa. One of the early Okinawan masters, To-De Sakugawa (1733-1815) is credited as being one of the initial importers of Chinese martial arts to Okinawa, in particular to Shuri, where he started the development of the Shuri-Te style of Okinawan martial arts.

Sakugawa had a student named Sokon Matsumura, who in turn taught Anko Itosu who was destined to become a great martial artist and teacher in the 19th century, who introduced the practice of To-De, as the Okinawan martial arts were called, to the Okinawan school system. Ankoh Itosu’s contribution to To-De was the emphasis of Kata and its practical application, called Bunkai.

Many students of Ankoh Itosu became significant figures in the early development of karate.Amongst Itosu’s students are Gichin Funakoshi (1867-1957), who later moved to Japan and founded Shotokan Karate, and Kenwa Mabuni (1890-1954), combined aspects of Naha-Te and Shuri-Te, also moved to Japan, and founded Shito-Ryu Karate

Important Okinawan masters of Shuri-te:

Sakukawa Kanga, Matsumura Sōkon, Itosu Ankō, Asato Ankō, Chōyū Motobu, Motobu Chōki, Yabu Kentsū, Chōmo Hanashiro, Funakoshi Gichin, Kyan Chōtoku, Chibana Chōshin, Mabuni Kenwa, Tōyama Kanken, Tatsuo Shimabuku

The successor styles to Shuri-te include Shōtōkan-ryū, Shōtōkai, Wadō-ryū, Shitō-ryū, Motobu-ryū, Shuri-ryū, Shōrin-ryū, Shudokan, Keishinkan, and Shōrinji-ryū.

Important Katas:

Naihanchi (más tarde Tekki), Pinan (más tarde Heian), Kusanku (más tarde Kanku), Passai (más tarde Bassai), Jion, Jitte, Sochin, Chinto

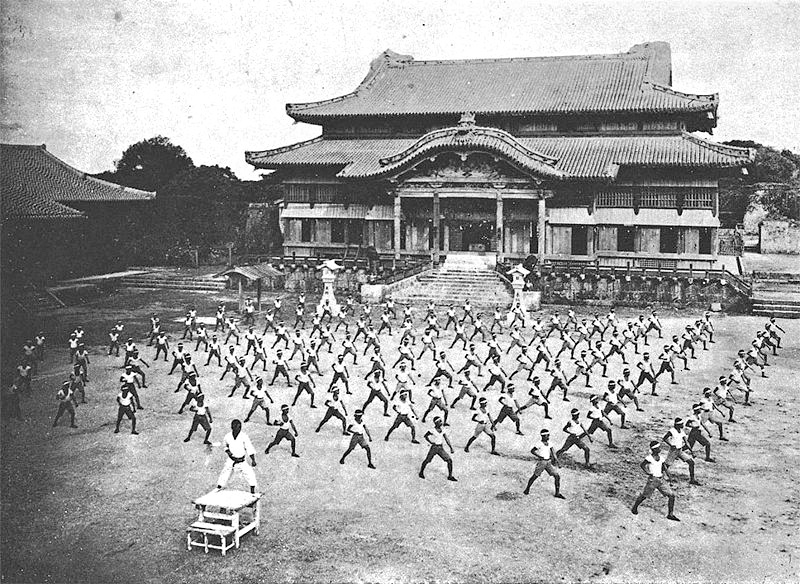

Karate training with Shinpan Gusukuma sensei at Shuri Castle 1938, Okiinawa Prefecture, Japan

Important Okinawan Masters of Shuri-te

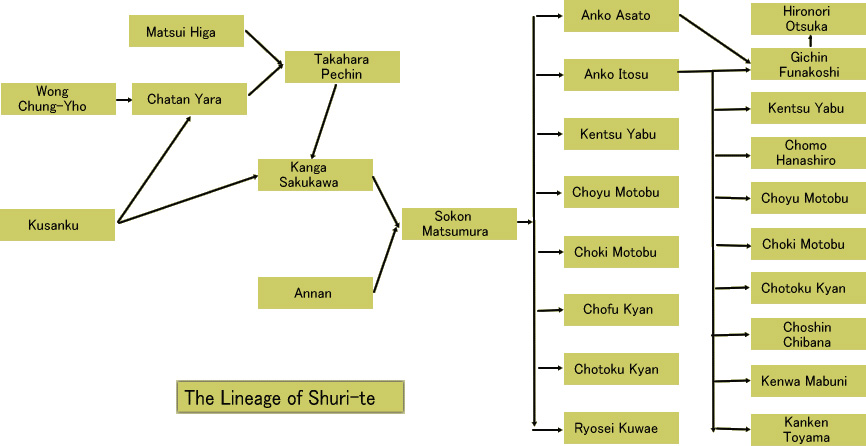

Wong Chung-Yoh was a 17th century teacher of a style of martial arts known as xingyiquan. Located in Fuzhou in the Fukien Province of China, he was notable for being the teacher of Chatan Yara.

Kūsanū (クーサンクー、公相君), (1720-1790) also known as Kwang Shang Fu, was a Chinese martial

Kūsanū (クーサンクー、公相君), (1720-1790) also known as Kwang Shang Fu, was a Chinese martial

artist who lived during the 18th century. He is credited as having an influence on virtually all karate-derived martial arts.

Kūsankū learned the art of Ch’uan Fa in China from a Shaolin monk. He was thought to have resided (and possibly studied martial arts) in the Fukien province for much of his life.Around 1756, Kūsankū was sent to Okinawa as an ambassador of the Qing Dynasty. He resided in the village of Kanemura, near Naha City. During his stay in Okinawa, Kūsankū instructed Kanga Sakukawa.

Sakugawa trained under Kūsankū for six years.After Kūsankū’s death (around 1762), Sakugawa developed and named the Kusanku kata in honor of his teacher.

Chatan Yara (北谷 屋良)(1740 – 1812), (aka Yara Guwa, Ueekata Yomitan Yara), is credited with being one of the first to disseminate the art of Te throughout Okinawa Yara is most noted for teaching Takehara Peichin who would later be the sensei of Sakugawa Kanga the father of Okinawan karate. Depending on Sakugawa’s birth date, Yara may have been his teacher also (based on the kata he taught).Yara was from Chatan Village, on Okinawa Island.

According to most accounts, Yara’s parents sent him to China at the age of 12 under the advice of his uncle to study the Chinese language and the martial arts. It was here he mastered the use of a the bo staff and twin sais under the guidance of his teacher Wong Chung-Yoh.

Shortly after returning to Shuri around 1800, Yara came to the assistance of a woman being harassed by a samurai. First avoiding the samurai’s sword attacks, Yara acquired an eku (oar) from a nearby boat and successfully disarmed and killed the samurai. Soon after this rescue, he was recruited by local officials to teach his martial art to the local community for the purpose of self-defense.

In any case, he contributed much to Okinawa karate. He reportedly studied in China for 20 years. His bo and sai techniques greatly influenced Okinawan kobudo, his Kata, „Chatan Yara No Sai,” „Chatan Yara Sho No Tonfa,” and „Chatan Yara No Kon” are widely practiced today.

Higa Peechin (比嘉 親雲上) (1790–1870), often called Machuu Hijaa (マチュー ヒジャー) or (Matsu Higa) is a semi-legendary martial artist in Okinawan history who was a direct influence on the development of karate and kobudo, especially with respect to bojutsu. Pechin (親雲上 Peechin) is social class of Ryukyu Kingdom.A resident of the island of Hama Higa, he was perhaps a student of the Chinese emissaries Zhang Xue Li and later Wanshu, who would have taught him techniques of chu’an fa.

Okinawan history relied mainly on oral tradition prior to the 20th century, so it is difficult to separate fact and fiction (or embellishment). It is said that Matsu Higa had forearms like tree trunks and that he could crush a coconut in his bare hands, though he stood only 5 feet 2 inches (157 cm) tall and weighed about 140 pounds (64 kg). Legends state that Matsu Higa with his bo stood up to the head-hunters of Formosa and to Japanese pirates from the north and never lost a battle.

What is known, however, is that Matsu Higa was the teacher of Takahara Peechin, who in turn taught Sakugawa Kanga. Matsu Higa was one of the first to codify a system of kata and techniques. His contributions live on in several weapons katas, especially for tonfa, sai and bo.

Takahara Pēchin (高原 親雲上) (1683-1760)

Takahara Pēchin was revered as a great warrior and is attributed to have been the first to explain the aspects or principles of the word do („way”). These principals are: (1) ijo, the way-compassion, humility and love. (2) katsu, the laws-complete understanding of all techniques and forms of karate, and (3) fo, dedication seriousness of karate that must be understood not only in practice, but in actual combat. The collective translation is: „One’s duty to himself and his fellow man.” Most importantly, he was the first teacher of Sakugawa, Kanga „Tode” who was to become known as the „father of Okinawan karate.”

Pēchin was a social class of the Ryukyu Kingdom

Kanga Sakugawa (佐久川 寛賀)

Kanga Sakugawa (佐久川 寛賀)

Kanga Sakugawa (1733 – 1815), also Sakugawa Satunushi and Tode Sakugawa, was an Okinawan martial arts master and major contributor to the development of Te the precursor to modern karate.

.In 1750, Sakukawa (or Sakugawa) began his training as a student of an Okinawan monk, Peichin Takahara. After six years of training, Takahara suggested that Sakugawa train under Kusanku, a Chinese master in Ch’uan Fa. Sakukawa spent six years training with Kusanku, and began to spread what he learned to Okinawa in 1762. He became a such expert that people gave him, as a nickname: „Tōde” Sakugawa (Sakugawa „Chinese Hand”). His most famous student, Matsumura Sokon, went on to develop the Shuri-te which later develop into Shorin-ryu style of karate.

Chintō (In Shotokan, Gankaku (岩鶴) is an advanced kata practiced in many styles of Karate. According to legend, it is named after a Chinese sailor, sometimes referred to as Annan, whose ship crashed on the Okinawan coast. To survive, Chintō stole from the crops of the local people. Matsumura Sokon, a Karate master and chief bodyguard to the Okinawan king, was sent to defeat Chintō. In the ensuing fight, however, Matsumura found himself equally matched by the stranger, and consequently sought to learn his techniques.

It is known that the kata Chintō was well known to the early Tomari-te and Shuri-te schools of Karate. Matsumura Sōkon was an early practitioner of the Shuri-te style. When Gichin Funakoshi brought Karate to Japan, he renamed Chintō (meaning approximately „fighter to the east”) to Gankaku (meaning „crane on a rock”), possibly to avoid anti-Chinese sentiment of the time. He also modified the actual pattern of movement, or embusen, to a more linear layout, similar to the other Shotokan kata.The kata is very dynamic, employing a diverse number of stances (including the uncommon crane stance), unusual strikes of rapidly varying height, and a rare one-footed pivot. Bunkai generally describes this kata as being useful on uneven, hilly terrain.It is often said that Chintō should be performed while facing eastwards.

Today, Chintō is practiced in Wado-ryu , Shukokai, Isshin-ryu, Chito-ryu, Shorin-ryu, Shito-ryu, Shotokan (Gankaku), Gensei-ryu and Yoshukai.

Matsumura Sōkon (松村 宗棍)

Matsumura Sōkon (松村 宗棍)

Matsumura Sōkon was one of the original karate masters of Okinawa. His life is reported variously as (c.1809-1901) or (1798–1890) or (1809–1896) or (1800–1892

Matsumura Sōkon was born in Yamagawa Village, Shuri, Okinawa. Matsumura began the study of karate under the guidance of Sakukawa Kanga (1762–1843) or (1733–1815) or (1782–1837). Sakukawa was an old man at the time and reluctant to teach the young Matsumura, who was regarded as something of a troublemaker. However, Sakukawa had promised Matsumura Sōfuku, Matsumura Sōkon’s father, that he would teach the boy, and thus he did. Matsumura spent five years studying under Sakukawa. As a young man, Matsumura had already garnered a reputation as an expert in the martial arts

Matsumura was recruited into the service of the Shō family, the royal family of the Ryukyu Kingdom in 1816 and received the title Shikudon (also Chikudun Pechin), a gentry rank.

He began his career by serving the 17th King of Ryūkyū’s second Shō dynasty, King Sho Ko. In 1818 he married Yonamine Chiru, who was a martial arts expert as well. Matsumura eventually became the chief martial arts instructor and bodyguard for the Okinawan King Shō Kō. He subsequently served in this capacity for the last two Okinawan kings, Shō Iku and Sho Tai. Matsumura traveled on behalf of the royal government to Fuzhou and Satsuma. He studied Chuan Fa in China as well as other martial arts and brought what he learned back to Okinawa.

He was the first to introduce the principles of Satsuma’s swordsmanship school, Jigen-ryu, into Ryukyu kobujutsu (Ryūkyūan traditional martial arts) and he is credited with creating the foundation for the bojutsu of Tsuken. He passed on Jigen-ryū to some of his students, including Anko Asato and Itarashiki Chochu. The Tsuken Bō tradition was perfected by Tsuken Seisoku Ueekata of Shuri

Matsumura is credited with passing on the Shorin-ryu Kempo-karate know as naihanchi Ⅰ&Ⅱ,passai, seisan, chinto, gogushuho, kusanku (the embodiment of kusanku’s teaching as passed on to Tode Sakugawa) and hakutsuru kata kata contains the elements of the Fujian White Crane system taught within the Shaolin system of Chinese kempo.Another set of kata,known as chanan in Matsumura’s time,is said to have been devised by Matsumura himself and was the basis for pinan Ⅰ and Ⅱ .Matsumura’s style has endured to the above mentioned kata are the core of Shorin-ryu karate today.

Matsumura was given the title bushi meaning „warrior” by the Okinawan king in recognition of his abilities and accomplishments in the martial arts.Described by Gichin Funakoshi as a sensei with a terrifying presence, Matsumura was never defeated in a duel, though he fought many. Tall, thin, and possessing a pair of unsetting eyes, Matsumura was described by his student Anko Itosu as blindingly fast and deceptivly strong. His martial arts endeavors have been the progenitor of many contemporary karate styles: Shorin-ryu, shotokan-ryu and Shito-ryu,for example. Ultimatly, all modern styles of karate that evolved from the Shuri-te lineage can be traced back to the teachings of Bushi Matsumura. Of note his grandson was the modern Tode master, Tsuyoshi Chitose, who assisted Gichin Funakoshi in the early introduction and teaching of the karate in Japan and who founded the Chito-ryu (千唐流) style.

Anko Asato (安里 安恒)

Anko Asato (AzatoYasutsune in 1827 – 1906) was an Okinawan master of karate. He and Anko Itosu were the two main karate masters who taught Gichin Funakoshi, the founder of Shotokan-ryu karate. Funakoshi appears to be the source of most of the information available on Asato. Many articles contain information about Asato but the relevant parts are clearly based on Funakoshi’s descriptions of him.

Funakoshi first met Asato when he was a schoolmate of Asato’s son; he called Asato „one of Okinawa’s greatest experts in the art of karate. According to Funakoshi, Asato’s family belonged to the Tonochi class (hereditary town and village chiefs), and held authority in the village of Asato, halfway between Shuri and Naha, and he was not only a master of karate, but also skilled at riding horses, Jigen-ryu kendo (swordsmanship), archery, and an exceptional scholar

In a 1934 article, Funakoshi noted that Asato and Itosu had studied karate together under Sokon Matsumura. He also related how Asato and Itosu once

overcame a group of 20–30 attackers,and how Asato set a trap for troublemakers in his home village. In his 1956 autobiography, Funakoshi recounted several stories about Asato, including: Asato’s political astuteness in following the government order to cut off the traditional men’s topknot .Asato’s defeat of Yōrin Kanna, in which the unarmed Asato prevailed despite Kanna being armed with an unblunted blade Asato’s demonstration of a single-point punch and Asato and Itosu’s friendly arm-wrestling matches

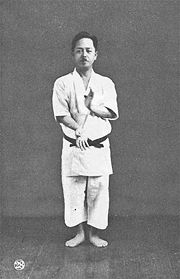

Ankō Itosu (糸洲 安恒) Grand Father of modern karate

Ankō Itosu (糸洲 安恒) Grand Father of modern karate

Itosu Ankō, 1831 – 1915) is considered by many the father of modern karate, although this title is also often given to Gichin Funakoshi because the latter spread karate throughout Japan

Itosu was born in 1831 and died in 1915. Ethnically Okinawan, Itosu was small in stature, shy, and introverted as a child. He was raised in a strict home of the keimochi (a family of position), and was educated in the Chinese classics and calligraphy. Itosu began his Tode (karate) study under Nagahama Chikudun Pechin. His study of the art led him to Sokon Matsumura. Part of Itosu’s training was makiwara practice. He once tied a leather sandal to a stone wall in an effort to build a better makiwara. After several strikes, the stone fell from the wall. After relocating the sandal several times, Itosu had destroyed the wall.

Itosu served as a secretary to the last king of the Ryukyu Islands until Japan abolished the Okinawa-based native monarchy in 1879. In 1901, he was instrumental in getting karate introduced into Okinawa’s schools. In 1905, Itosu was a part-time teacher of To-te at Okinawa’s First Junior Prefectural High School. It was here that he developed the systematic method of teaching karate techniques that are still in practice today.

He created and introduced the Pinan forms (Heian in Japanese) as learning steps for students, because he felt the older forms (kata in Japanese) were too difficult for schoolchildren to learn. The five Pinan forms were created by drawing from two older forms: kusanku and chiang nan. Itosu is also credited with taking the large Naihanchi form (tekki in Japan) and breaking it into the three well-known modern forms Naihanchi Shodan, Naihanchi Nidan, and Naihanchi Sandan. In 1908, Itosu wrote the influential „Ten Precepts (Tode Jukun) of Karate,” reaching beyond Okinawa to Japan. Itosu’s style of karate, Shorin-ryu, came to be known as Itosu-ryu in recognition of his skill, mastery, and role as teacher to many.

While Itosu did not invent karate himself, he modified the kata (forms) he learned from his master, Matsumura, and taught many karate masters. Itosu’s students included:

Choyu Motobu (1857–1927), Choki Motobu (1870–1944), Kentsu Yabu (1866–1937), Gichin Funakoshi (1868–1957),Chomo Hanashiro (1869–1945), Moden Yabiku (1880–1941), Kanken Toyama (1888–1966), Chotoku Kyan (1870–1945), Shinpan Shiroma (gusukuma) (1890–1954), Anbun Tokuda (1886–1945), Kenwa Mabuni (1887–1952), and Choshin Chibana (1885–1969).

In October 1908, Itosu wrote a letter, „Ten Precepts (Tode Jukun) of Karate,” to draw the attention of the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of War in Japan. A translation of that letter reads:

Ten Precepts of Karate (Tode Jukun)

Karate did not develop from Buddhism or Confucianism. In the past the Shorin-ryu school and the Shorei-ryu school were brought to Okinawa from China. Both of these schools have strong points, which I will now mention before there are too many changes:

1. Karate is not merely practiced for your own benefit; it can be used to protect one’s family or master. It is not intended to be used against a single assailant but instead as a way of avoiding a fight should one be confronted by a villain or ruffian.

2. The purpose of karate is to make the muscles and bones hard as rock and to use the hands and legs as spears. If children were to begin training in Tang Te while in elementary school, then they will be well suited for military service. Remember the words attributed to the Duke of Wellington after he defeated Napoleon: „The Battle of Waterloo was won on the playing fields of Eton.”

3. Karate cannot be quickly learned. Like a slow moving bull, it eventually travels a thousand miles. If one trains diligently every day, then in three or four years one will come to understand karate. Those who train in this fashion will discover karate.

4. In karate, training of the hands and feet are important, so one must be thoroughly trained on the makiwara. In order to do this, drop your shoulders, open your lungs, take hold of your strength, grip the floor with your feet, and sink your energy into your lower abdomen. Practice using each arm one to two hundred times each day.

5. When one practices the stances of Tang Te, be sure to keep your back straight, lower your shoulders, put strength in your legs, stand firmly, and drop your energy into your lower abdomen.

6. Practice each of the techniques of karate repeatedly, the use of which is passed by word of mouth. Learn the explanations well, and decide when and in what manner to apply them when needed. Enter, counter, release is the rule of releasing hand (torite).

7. You must decide if karate is for your health or to aid your duty.

8. When you train, do so as if on the battlefield. Your eyes should glare, shoulders drop, and body harden. You should always train with intensity and spirit, and in this way you will naturally be ready.

9. One must not overtrain; this will cause you to lose the energy in your lower abdomen and will be harmful to your body. Your face and eyes will turn red. Train wisely.

10. In the past, masters of karate have enjoyed long lives. Karate aids in developing the bones and muscles. It helps the digestion as well as the circulation. If karate should be introduced beginning in the elementary schools, then we will produce many men each capable of defeating ten assailants. I further believe this can be done by having all students at the Okinawa Teachers’ College practice karate. In this way, after graduation, they can teach at the elementary schools at which they have been taught. I believe this will be a great benefit to our nation and our military. It is my hope you will seriously consider my suggestion.

Anko Itosu, October 1908This letter was influential in the spread of karate

Motobu Chōyū (本部朝勇)

Motobu Chōyū (本部朝勇)

Motobu Choyo (1857-1928) was an Okinawan karate master and elder brother of karateka Motobu Chōki.

Motobu Chōyū was born in Akahira village in Shuri, Okinawa. His father, Anji (Lord) Motobu Chōshin was a descendent of Prince Shō Kōshin (1655-1687), the sixth son of Okinawan King Shō Shitsu (1629-1668).

Chōyū first learned the art of Te (the precursor to modern karate), which was passed down within the Shō royal family from father to eldest son. He then studied Shuri-te karate and koryū („old school”) Japanese martial arts under the legendary karateka Matsumura Sōkon.

He later combined all these arts he had learned to create the Motobu-ryū style of karate. In his final years, he was the

headmartial arts instructor to the last king of the Ryūkyū Kingdom, Shō Tai (1848-1879), succeeding Matsumura in

that position.

Matsumora Kōsaku(1829 – 1898) was an Okinawan karate master. He studied Tomari-te under Karyu Uku (aka Giko Uku) and Kishin Teruya. He also studied Jigen-ryu. Among Matsumora’s students, who went on to influence new generations through students of their own, were Choki Motobu and Chotoku Kyan.

Kentsū Yabu (屋部 憲通)

Kentsū Yabu (屋部 憲通)

Kentsū Yabu (Yabu Kentsū September 23, 1866 – August 27, 1937) was a prominent teacher of Shōrin-ryū karate in Okinawa from the 1910s until the 1930s, and was among the first people to demonstrate karate in Hawaii.

Yabu was born in Shuri, Okinawa, on September 23, 1866. He was the oldest son of Yabu Kenten and Shun Morinaga. He had three brothers, three sisters, and three half-sisters. On March 19, 1886, he married Takahara Oto (1868-1940).

As a young man, Yabu received training in Shōrin-ryū karate. His teachers included both Matsumura Sōkon and Itosu Anko.

Yabu joined the Japanese Army in 1891. He served in Manchuria during the First Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895. He received promotion to lieutenant, but to subsequent students, he was often known as gunso, or sergeant.

Following separation from the service, Yabu studied at Shuri’s Prefectural Teacher’s Training College, and in 1902, he became a teacher at Shuri’s Prefectural School Number One.

In 1908, Yabu’s oldest son, Kenden, went to Hawaii. In 1912, Kenden went to California. In the USA, Kenden Yabu became known as Kenden Yabe, after a method of transliteration then being used on Japanese passports.

In 1919, Kenden Yabe married, and in 1921, his wife became pregnant. Yabu Kentsu immediately went to California to visit his son (and, hopefully, grandson). However, Kenden Yabe and his wife only had daughters. Thus, Yabu Kentsu went back to Okinawa disappointed.

Yabu visited the United States twice, once during 1921-1922, and again in 1927. During the second visit, he returned to Okinawa via Hawaii. He spent about nine months in the Territory. He spent most of his time on Oahu, but he also visited other islands. In Honolulu, he gave two public demonstrations of karate at the Nuuanu YMCA..

In 1936, Yabu visited Tokyo. While there, he visited the young Shōshin Nagamine, who later became another well-known karate teacher. Yabu died at Shuri, Okinawa, on August 27, 1937.

As a former soldier, Yabu has been credited with helping make Okinawan karate training more militaristic. That is, students were expected to line up in rows, and respond by the numbers. If so, this was probably part of the general militarization of Japanese athletics common during the early 20th century. However, there is no doubt that his methods involved much rote repetition. His favorite kata reportedly included Gojūshiho and naihanchi

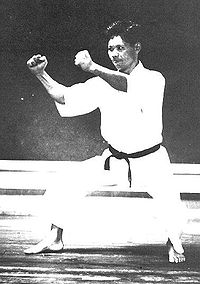

Gichin Funakoshi (船越 義珍) Father of modern karate

Gichin Funakoshi (船越 義珍) Father of modern karate

Gichin Funakoshi (Funakoshi Gichin November 10, 1868 – April 26, 1957) was the creator of Shotokan karate, perhaps the most widely known style of karate, and is attributed as being the ‘father of modern karate. Following the teachings of Anko Itosu, he was one of the Okinawan karate masters who introduced karate to the Japanese mainland in 1921. He taught karate at various Japanese universities and became honorary head of the Japan Karate Association upon its establishment in 1949.

Gichin Funakoshi was born in Shuri, Okinawa in the year of the Meiji Restoration around 1868 to ethnic Okinawan parents and originally had the family name Tominakoshi. His father’s name was Gisu. After entering primary school he became close friends with the son of Ankō Asato, a karate and kendo master who would soon become his first karate teacher.

Funakoshi’s family was stiffly opposed to the abolition of the Japanese topknot, and this meant he would be ineligible to pursue his goal of attending medical school, despite having passed the entrance examination. Being trained in both classical Chinese and Japanese philosophies and teachings, Funakoshi became an assistant teacher in Okinawa. During this time, his relations with the Asato family grew and he began nightly travels to the Asato family residence to receive karate instruction from Ankō Asato

Funakoshi had trained in both of the popular styles of Okinawan karate of the time: Shorei-ryu and Shorin-ryu. Shotokan is named after Funakoshi’s pen name, Shoto, which means „pine waves” or „wind in the pines”. In addition to being a karate master, Funakoshi was an avid poet and philosopher who would reportedly go for long walks in the forest where he would meditate and write his poetry. Kan means training hall, or house, thus Shotokan referred to the „house of Shoto”. This name was coined by Funakoshi’s students when they posted a sign above the entrance of the hall at which Funakoshi taught reading „Shoto kan”.

By the late 1910s, Funakoshi had many students, of which a few were deemed capable of passing on their master’s teachings. Continuing his effort to garner widespread interest in Okinawan karate, Funakoshi ventured to mainland Japan in 1922.

In 1930, Funakoshi established an association named Dai-Nihon Karate-do Kenkyukai to promote communication and information exchange among people who study karate-do. In 1936 Dai-Nippon Karate-do Kenkyukai changed its name to Dai-Nippon Karate-do Shoto-kai. The association is known today as Shotokai. Shotokai is the official keeper of Funakoshi’s Karate-do heritage.

In 1939, Funakoshi built the first Shōtōkan dojo in tokyo. He changed the name of karate to mean „empty hand” instead of „China hand” (as referred to in Okinawa); the two words sound the same in Japanese, but are written differently. It was his belief that using the term for „Chinese” would mislead people into thinking karate originated with Chinese boxing, Karate had borrowed many aspects from Chinese boxing which the original creators say as being positive, as they had done with other martial arts. In addition, Funakoshi argued in his autobiography that a philosophical evaluation of the use of „empty” seemed to fit as it implied a way which was not tethered to any other physical object.

Funakoshi’s interpretation of the word kara to mean „empty” was reported to have caused some recoil in Okinawa, prompting Funakoshi to remain in Tokyo indefinitely. His extended stay eventually led to the creation of the Japan Karate Association (JKA) in 1949 with Funakoshi as the honorary head of the organization. Funakoshi was not supportive of all of the changes that the organization eventually made to his karate style. He remained in Tokyo until his death in 1957. After World War II, Funakoshi’s surviving students formalized his teachings.

Funakoshi published several books on karate including his autobiography, Karate-Do: My Way of Life. His legacy, however, rests in a document containing his philosophies of karate training now referred to as the niju kun, or „twenty principles”. These rules are the premise of training for all Shotokan practitioners and are published in a work titled The Twenty Guiding Principles of Karate. Within this book, Funakoshi lays out 20 rules by which students of karate are urged to abide in an effort to „become better human beings” Funakoshi’s Karate-Do Kyohan „The Master Text” remains his most detailed publication, containing sections on history, basics and kata and kumite. The famous Shotokan Tiger by Hoan adorns the hardback cover.

A memorial to Gichin Funakoshi was erected by the Shotokai at Engaku-ji, a temple in Kamakura, on December 1, 1968. Designed by Kenji Ogata the monument features calligraphy by Funakoshi and Sōgen Asahina (1891–1979), chief priest of the temple which reads Karate ni sente nashi (There is no first attack in karate), the second of Funakoshi’s Twenty Precepts. To the right of Funakoshi’s precept is a copy of the poem he wrote on his way to Japan in 1922.

A second stone features an inscription by Nobuhide Ohama and reads:

Funakoshi Gichin Sensei, of karate-do, was born on June 10, 1870, in Shuri Okinawa. From about eleven years old he began to study to-te jutsu under Azato Anko and Itosu Anko. He practiced diligently and in 1912 became the president of the Okinawan Shobukai. In May of 1922, he relocated to Tokyo and became a professional teacher of karate-do. He devoted his entire life to the development of karate-do. He lived out his eighty-eight years of life and left this world on April 26, 1957. Reinterpreting to-te jutsu, the Sensei promulgated karate-do while not losing its original philosophy. Like bugei (classical martial arts), so too is the pinnacle of karate “mu” (enlightenment): to purify and make one empty through the transformation from “jutsu” to “do”. Through his famous words “Karate ni sente nashi” (There is no first attack in Karate) and “Karate wa kunshi no bugei” (Karate is the martial art of intelligent people), Sensei helped us to better understand the term “jutsu.” In an effort to commemorate his virtue and great contributions to modern karate-do as a pioneer, we, his loyal students, organised the Shotokai and erected this monument at the Enkakuji. “Kenzen ichi” (“The fist and Zen are one”)

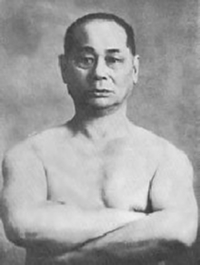

Motobu Chōki (本部 朝基)

Motobu Chōki (本部 朝基)

The Okinawan karateka Motobu Chōki (1870-1944), younger brother of karateka Motobu Chōyū, was born in Akahira Village in Shuri, Okinawa, then capital of the Ryūkyū Kingdom.

His father, Lord Motobu Chōshin (Motobu Aji Chōsin) was a descendant of the sixth son of the Okinawan King, Shō Shitsu (1629–1668), namely Shō Kōshin, also known as Prince Motobu Chōhei (1655–1687). Chōki was the third son of Motobu Udun („Motobu Palace”), one of cadet branches of the royal Okinawan Shō family.

As the last of three sons, Motobu Chōki was not entitled to an education in his family’s style of Te (an earlier name for karate). Despite this Motobu was very interested in the art, spending much of his youth training on his own, hitting the makiwara, and lifting heavy stones to increase his strength. He is reported to have been very agile, which gained him the nickname Motobu no Saru, or „Motobu the Monkey.” He began practicing karate under Ankō Itosu and continued under Matsumura Sōkon, Sakuma Pechin and Kōsaku Matsumora

Although he was reputed by his detractors to have been a violent and crude street fighter, with no formal training, Motobu was a student of several of Okinawa’s most prominent karate practitioners. Ankō Itosu (1831–1915), Sōkon Matsumura (1809–1899), Sakuma Pechin, Kōsaku Matsumora (1829–1898), and Tokumine Pechin (1860–1910) all taught Motobu at one time or another. Many teachers found his habit of testing his fighting prowess via street fights in the tsuji (red light district) undesirable, but his noble birth (as a descendant of the royal Okinawan Shō family) may have made it hard for them to refuse.

Popular myth holds that Motobu only knew one kata, Naifanchi (Naihanchi). Although he favored this kata, and called it „the fundamental of karate,” he also made comments on the practice of Passai,(Bassai) Chintō, and Rōhai. Other sources describe Sanchin, Kusanku, and Ueseishi as having been part of his repertoire. He apparently developed his own kata, Shiro Kuma (White Bear). Motobu lived and taught karate in Japan until 1941, when he returned to Okinawa, dying shortly thereafter. Prior to this, he had made several trips there to study orthodox kata and kobudō in an effort to preserve the traditional forms of the art

After a number of failed business enterprises, Motobu moved to Osaka, Japan, in 1921. A friend convinced Motobu to enter a „boxing vs judo” match which was taking place. These matches were popular at the time, and often pitted a visiting foreign boxer against a jujutsu or judo man. According to an account of the fight from a 1925 King magazine article, Motobu is said to have entered into a challenge match with a foreign boxer, described as a Russian boxer or strongman. Early rounds involved evasion by the smaller man, but after a few rounds, according to the account, Motobu moved in on the taller, larger boxer and knocked him out with a single hand strike to the head. Since reporters were not familiar with karate at that time, it is also possible that Motobu kicked the taller man in the groin to enable striking the head. Motobu was then 52 years old.

The King article detailed Motobu’s surprising victory, although the illustrations clearly show Gichin Funakoshi as the Okinawan fighter in question. This publication error increased the bitter rivalry between the two men, and led to an apparent confrontation. The two were often at odds in their opinions about how karate ought to be taught and used.

The popularity generated by this unexpected victory propelled both Motobu and karate to a degree of fame that neither had previously known in Japan. Motobu was petitioned by several prominent individuals, including boxing champ „Piston” Horiguchi, to begin teaching. He opened a dojo, the Daidokan, where he taught until the onset of World War II in 1941. Motobu faced considerable difficulties in his teaching. Chief among those was his inability to read and speak mainland Japanese. Okinawan dialects are nearly incomprehensible to mainlanders. As a result, much of his instruction was through translators, which led to the rumor that he was illiterate. This rumor has been largely discredited by the existence of samples of Motobu’s handwriting, which is in a clear and literate hand. In a Tsunami video production on the Motobu style, Motobu Chōsei comments that his father’s language difficulties may have been motivated more by protest at being a displaced member (by the Japanese annexation of Okinawa) of the Ryukyuan aristocracy than by inability

Motobu Chōki’s third son, Chōsei Motobu (1925- ), still teaches the style that his father passed on to him. As a point of reference, it is important to distinguish between the „Motobu-ryū” which Chōsei teaches, and „Motobu Udun Di”, the unique style of the Motobu family, which bears a resemblance to aikijutsu. Now Chōsei Motobu is the second Sōke of Motobu-ryū and the 14th Sōke of Motobu Udun Di.

Motobu’s karate is marked by a series of two man kumite drills, which were an advancement in the popular thinking and instructional methods of the time. His curriculum heavily favored the Naihanchi kata because of the correspondence between its applications (bunkai) and actual fighting, which he experienced in brawls as a young man. Below are some of his ideas regarding the ‘kata:

– „The position of the legs and hips in Naifuanchin (the old name for Naihanchi) no Kata is the basics of karate.”

– „Twisting to the left or right from the Naifuanchin stance will give you the stance used in a real confrontation. Twisting ones way of thinking about Naifuanchin left and right, the various meanings in each movement of the kata will also become clear.”

– „The blocking hand must be able to become the attacking hand in an instant. Blocking with one hand and then countering with the other is not true bujutsu. Real bujutsu presses forward and blocks and counters in the same motion.”

– Motobu Chōki’s third son, Chōsei Motobu (1925- ), still teaches the style that his father passed on to him. As a point of reference, it is important to distinguish between the „Motobu-ryū” which Chōsei teaches, and „Motobu Udun Di”, the unique style of the Motobu family, which bears a resemblance to aikijutsu. Now Chōsei Motobu is the second Sōke of Motobu-ryū and the 14th Sōke of Motobu Udun Di.

Motobu’s karate is marked by a series of two man kumite drills, which were an advancement in the popular thinking and instructional methods of the time. His curriculum heavily favored the Naihanchi kata because of the correspondence between its applications (bunkai) and actual fighting, which he experienced in brawls as a young man. Below are some of his ideas regarding the ‘kata:

– Motobu trained many students who went on to become noteworthy practitioners of karate in their own right, including:

– Nakamura Shigeru, founder of Okinawa Kenpo

– Tatsuo Yamada, founder of Nihon Kenpo Karate-dō

– Sannosuke Ueshima, founder of Kushin-ryū

– Yasuhiro Konishi, founder of Shindō jinen-ryū

– Kose Kokuba (Yukimori Kuniba), founder of Seishin Kai

– Hironori Ōtsuka, founder of Wadō-ryū

– Tatsuo Shimabuku, founder of Isshin-ryū

– Shōshin Nagamine, founder of Matsubayashi-ryū

– Katsuya Miyahira, founder of Shōrin-ryū Shidōkan

Chotoku Kyan (喜屋武 朝徳)

Chotoku Kyan (喜屋武 朝徳)

Chotoku Kyan (Kyan Chōtoku) born December 1870 in Shuri, Okinawa – September 20, 1945 in Ishikawa, Okinawa) was an Okinawan karate master who was famous for both his karate skills, and his colorful personal life. Chotoku Kyan (also spelled Chotoku Kiyan) was a large influence in the styles of karate that would become Shorin-Ryu and its related styles.

Chotoku Kyan was born as the first son of Chofu Kyan who was a steward to the Ryukyuan King before the realm’s official assimilation into Japan as the Okinawan Prefecture. Kyan was noted for being small in stature, suffering from asthma and frequently bed-ridden. He also had poor eyesight, which may have led to his early nickname Chan Migwa (squinty-eyed Chan)

Kyan’s father is noted as possibly having a background in karate and even teaching Kyan tegumi in his early years. When Kyan was 20 years old, he began his karate training under Kosaku Matsumora and Kokan Oyadomari.

While at 30 years of age, he was considered a master of the karate styles known as Shuri-te and Tomari-te .The most long time student of Kyan was Zenryō Shimabukuro, who studied with Kyan for over 10 years. Kyan is also noted for encouraging his students to visit brothels and to engage in alcohol consumption at various times.

Kyan was a participant in the 1936 meeting of Okinawan masters, where the term „karate” was standardized, and other far-reaching decisions were made regarding martial arts of the island at the time.

Kyan survived the Battle of Okinawa in 1945, but died from fatigue and malnutrition in September of that year

Chōshin Chibana (知花 朝信)

Chōshin Chibana (知花 朝信)

Chōshin Chibana (Chibana Chōshin 1885 – 1969) was an Okinawan martial artist who developed Shorin-ryū karate based on what he had learned from Ankō Itosu.

Chibana was the last of the pre-World War karate masters, also called the „Last Warrior of Shuri” He was the first to establish a Japanese ryu name for an Okinawan karate style, calling Itosu’s karate „Shorin-Ryu” (or „the small forest style”) in 1928

Chibana Choshin was born June 5, 1885, into a distinguished family in Okinawa’s Shuri Tori-Hori village (presently Naha City, Shuri Tori-Hori Town). His family traced their lineage from a branch of the Katsuren Court and Choharu, Prince of Kochinta, fifth son of King Shoshitsu (Tei), but lost their titles and status after Mutsuhito, the Meiji Emperor, banned the caste system in Japan. To support themselves, the family turned to sake brewing.

Choshin began his study of martial arts under Ankō Itosu in 1889 when he was about fifteen years old. He applied and was accepted as a suitable candidate for instruction, and for thirteen years until he turned 28, Choshin trained under Itosu. When Itosu died at the age of 85, he continued to practice alone for five years, and then opened his first dojo in Tori-hori district at the age of 34. He later opened a second dojo in Kumojo district of Naha City

During the World War II Battle of Okinawa, Chibana lost his family, his livlihood, his dojo, a number of students, and nearly his life. He fled the war, but afterward returned to Shuri from Chinen Village and began teaching again. He first taught in the Gibo area, and then at ten other sites in the Yamakawa district of Shuri and Naha, eventually relocating his main headquarters (hombu dojo) from Asato to Mihara.

From February 1954 to December 1958, Chibana served as Karate Advisor and Senior Instructor for the Shuri Police Precinct. In May of 1956, the Okinawa Karate Federation was formed and he assumed office as its first President. Chibana was associated with Chotoku Kyan, with whom he performed karate demonstrations to promote Shorin-Ryu style of karate.

By 1957, Chibana had received the title of Hanshi (High Master) from the Dai Nippon Butokukai (The Greater Japan Martial Virtue Association). In 1960, he received the First Sports Award from the Okinawa Times Newspaper for his overall accomplishments in the study and practice of traditional Okinawan Karate-do. On April 29, 1968, was awarded the 4th Order of Merit by the Emperor of Japan in recognition of his devotion to the study and practice of Okinawan karate-do

In 1964, Chibana learned that he had terminal throat cancer, but he continued to teach students in his dojo. In 1966 he was admitted into Tokyo’s Cancer Research Center for radiation treatment and after some improvement, Chibana once again resumed teaching with the assistance of his grandson, Nakazato Akira (Shorin-ryu 7-Dan). By the end of 1968, Chibana-sensei’s condition worsened and he returned to Ohama Hospital and died at 6:40 a.m. on the 26 February 1969, at the age of 83

Kenwa Mabuni (摩文仁 賢和)

Kenwa Mabuni (摩文仁 賢和)

Kenwa Mabuni (Mabuni Kenwa1889 – 1952) was one of the first karateka to teach karate on mainland Japan and is creditied as developing the style known as Shitō-ryū (糸東流).

Kenwa Mabuni was a peer of Funakoshi Gichin (founder of Shotokan).

Funakoshi Gichin learned kata from Kenwa Mabuni: In order to expand his knowledge he sent his son Gigō to study kata in Mabuni’s dōjō in Osaka.

Kenwa Mabuni, Motobu Chōki and other Okinawans were actively teaching karate in Japan prior to this point when Gichin Funakoshi ‘officially’ brought karate from Okinawa to mainland Japan.

Shitō-ryū is a school of karate that was founded by Kenwa Mabuni in 1931. In 1939 the style was officially registered in the Butoku Kai headquarters.

Born in Shuri on Okinawa in 1889, Mabuni Sensei was a descendant of the famous Onigusukini Samurai family. Perhaps because of his weak constitution,

he began his instruction in his home town in the art of Shuri-Te at the age of 13, under the tutelage of the legendary Ankō Yasutsune Itosu(1813-1915). He trained diligently for several years, learning many kata from this great master. It was Itosu who first developed the Pinan kata, which were most probably derived from the ‘Kusanku’ form.

One of his close friends, Sensei Chōjun Miyagi(founder of Gōjū-ryū) introduced Mabuni to another great of that period, Sensei Higaonna Kanryō and began to learn Naha-Te under him as well. While both Itosu and Higashionna taught a ‘hard-soft’ style of Okinawan ‘Te’, their methods and emphases were quite distinct: the Itosu syllabus included straight and powerful techniques as exemplified in the Naifanchi and Bassai kata; the Higashionna syllabus, on the other hand, stressed circular motion and shorter fighting methods as seen in the popular Seipai and Kururunfa forms. Shitō-ryū focuses on both hard and soft techniques to this day.

Although he remained true to the teachings of these two great masters, Mabuni sought instruction from a number of other teachers; including Seishō Aragaki, Tawada Shimboku, Sueyoshi Jino and Wu Xianhui (a Chinese master known as Go-Kenki). In fact, Mabuni was legendary for his encyclopaedic knowledge of kata and their bunkai applications. By the 1920s, he was regarded as the foremost authority on Okinawan kata and their history and was much sought after as a teacher by his contemporaries. There is even some evidence that his expertise was sought out in China, as well as Okinawa and mainland Japan. As a police officer, he taught local law enforcement officers and at the behest of his teacher Itosu, began instruction in the various grammar schools in Shuri and Naha.

In an effort to popularize karate in mainland Japan, Mabuni made several trips to Tokyo in 1917 and 1928. Although much that was known as ‘Te’ (Chinese Fist) or Karate had been passed down through many generations with jealous secrecy, it was his view that it should be taught to anyone who sought knowledge with honesty and integrity. In fact, many masters of his generation held similar views on the future of Karate: Sensei Gichin Funakoshi (founder of Shotokan,another contemporary, had moved to Tokyo in the 1920s to promote their art on the mainland as well. During this period, Mabuni also taught many other prominent martial artists, such as Otsuka Hironori (founder of Wadō-ryū) and Konishi Yasuhiro (founder of Shintō Jinen-ryū). Both men were students of Funakoshi sensei.

By 1929, Mabuni had moved to Osaka on the mainland, to become a full-time karate instructor of a style he originally called Hanko-ryū, or ‘half-hard style’. In an effort to gain acceptance in the Japanese Butokukai, the governing body for all officially recognized martial arts in that country, he and his contemporaries decided to call their art ‘Karate’ or ‘Empty Hand’, rather than ‘Chinese Hand’, perhaps to make it sound more Japanese. Around the same time, perhaps when first introducing his style to the Butokukai, is when it’s believed the name of the style changed to Shitō-ryū, in honour of its main influences. Mabuni derived the name for his new style from the first Kanji character in their names, Itosu and Higashionna. With the support of Sensei-ryūsho Sakagami (1915-1993), he opened a number of Shitō-ryū dojo in the Osaka area, including Kansai University and the Japan Karate-dō Kai dojo. To this day, the largest contingent of Shitō-ryū practitioners in Japan is centred in the Osaka area. However, Mabuni’s contemporary Shinpan Shiroma remained in Shuri, Okinawa, and established Okinawan Shito-ryu

Mabuni published a number of books on the subject and continued to systematize the instruction method. In his latter years, he developed a number of formal kata, such as Aoyagi and Meijō, for example, which were designed specifically for women’s self defense. Perhaps more than any other Master in the last century, Mabuni was steeped in the traditions and history of Karate-do, yet forward thinking enough to realize that it could spread throughout the world. To this day, Shitō-ryū recognizes the influences of Itosu and Higashionna: the kata syllabus of Shito-ryū is still often listed in such a way as to show the two lineages.

Kenwa Mabuni died in 1952, and he is succeeded by his sons Kenei and Kenzo. His son Kenzo Mabuni died in 26 June, 2005, and was succeeded by his daughter

Hironori Ōtsuka (大塚 博紀)

Hironori Ōtsuka (大塚 博紀)

Ōtsuka Hironori June 1, 1892 – January 29, 1982) was a Japanese master of karate who created the Wadō-ryū style of karate. He was the first Grand Master of Wadō-ryū karate, and received high awards within Japan for his contributions to karate.

Ōtsuka was born on June 1, 1892, in Shimodate City, Ibaraki, Japan. He was one of four children to Tokujiro Ōtsuka, a medical doctor. At the age of 5 years, he began training in the martial art of jujutsu under his great-uncle, Chojiro Ebashi (a samurai). Ōtsuka’s father took over his martial arts education in 1897. At the age of 13, Ōtsuka became the student of Shinzaburo Nakayama in Shindō Yōshin-ryū jujutsu.

In 1911, while studying business administration at Waseda University in Tokyo, Ōtsuka trained in various jujutsu schools in the area. Before his studies were complete, his father died and he was unable to continue studying; he commenced work as a clerk at the Kawasaki Bank. Although he wished to become a full-time instructor, he did not pursue this course at this point out of respect for his mother’s wishes

Ōtsuka was born on June 1, 1892, in Shimodate City, Ibaraki, Japan. He was one of four children to Tokujiro Ōtsuka, a medical doctor. At the age of 5 years, he began training in the martial art of jujutsu under his great-uncle, Chojiro Ebashi (a samurai). Ōtsuka’s father took over his martial arts education in 1897.

At the age of 13, Ōtsuka became the student of Shinzaburo Nakayama in Shindō Yōshin-ryū jujutsu.

In 1911, while studying business administration at Waseda University in Tokyo, Ōtsuka trained in various jujutsu schools in the area. Before his studies were complete, his father died and he was unable to continue studying; he commenced work as a clerk at the Kawasaki Bank. Although he wished to become a full-time instructor, he did not pursue this course at this point out of respect for his mother’s wishes

On June 1, 1921, Ōtsuka received the menkyo kaiden (certificate of mastery and license to teach) in Shindō Yōshin-ryū jujutsu, and became the fourth master of that school. Jujutsu was not to become his primary art, however; in 1922, Ōtsuka began training in Shotokan karate under Gichin Funakoshi, who was a new arrival in Japan. In 1927, he also established a medical practice and specialized in treating martial arts training injuries.

By 1928, Ōtsuka was an assistant instructor in Funakoshi’s school. He also trained under Chōki Motobu and Kenwa Mabuni, and studied kobudo, around this time. Ōtsuka began to have philosophical disagreements with Funakoshi, and the two men parted ways in the early 1930s. This may have come, in part, from his decision to train with Motobu. Funakoshi’s karate emphasized kata, a series of movements and techniques linked by the fighting principles. Funakoshi did not believe that sparring was necessary for realistic training. Motobu, however, emphasized the necessity of free application, and created a series of two-person kumite called yakusoku kumite.

On April 1, 1934, Ōtsuka opened his own karate school the Dai Nippon Karate Shinko Kai at 63 Banchi Suehiro-Cho, Kanda, Tokyo. He blended Shotokan karate with his knowledge of Shindō Yōshin-ryū jujutsu to form Wadō-ryū karate, although the art would only later take on this name several years later. With recognition of his style as an independent karate style, Ōtsuka became a full-time instructor. In 1940, his style was registered at the Butokukai, Kyoto, for the demonstration of various martial arts, together with Shotokan, Shitō-ryū, and Gōjū-ryū.

Following World War II, the practice of martial arts in Japan was banned. After a few years, however, the ban was lifted; through the 1950s, Ōtsuka held various karate competitions. In 1964, three of Ōtsuka’s students (Tatsuo Suzuki, Toru Arakawa, and Hajime Takashima) from Nihon University toured Europe and the United States of America, demonstrating Wadō-ryū karate.

On April 29, 1966, Emperor Hirohito awarded Ōtsuka the Kun-Go-To (Fifth Order of Merit of the Sacred Treasure). The Emperor later also awarded him the Soko Kyokujitsu-Sho medal for his contributions to karate. In the next few years, Ōtsuka wrote two books on karate: Karate-Do, Volume 1 (1967, focused on kata) and Karate-Do, Volume 2 (1970, focused on kumite).

On October 9, 1972, the Kokusai Budo (International Martial Arts Federation) awarded Ōtsuka the title of Shodai Karate-do Meijin Judan (first-generation karate master 10th dan); this was the first time this honor had been bestowed on a karate practitioner.

Ōtsuka continued to teach and lead Wadō-ryū karate into the 1980s, and died on January 29, 1982. His son became the second Grand Master of Wadō-ryū karate and honored his father by taking the name „Hironori Ōtsuka

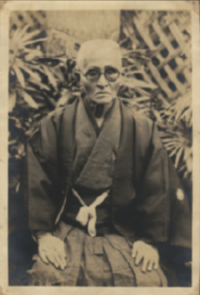

Kanken Tōyama (遠山寛賢)

Kanken Tōyama (遠山寛賢)

Kanken Tōyama (Tōyama Kanken, 24 September 1888 – 24 November 1966) was a Japanese schoolteacher and karate master, who developed the foundation for the Shūdōkan karate style. Born into a noble family in Shuri, Okinawa, Japan, he was given the name Oyadameri Kanken.

He trained under: Itosu Anko and Itarashiki primarily, and under Ankichi Aragaki, Azato Anko, Choshin Chibana, Oshiro, Tana, Yabu Kentsu, Yasutsune Itosu and Kanryo Higashionna.

Nine years old, he began his karate (Shuri-te) training under Ankō Itosu, and remained a student there until Itosu died in 1915. He also studied Naha-te under Kanryō Higaonna and Tomari-te under Ankichi Aragaki.

In 1924 Toyama moved his family to Taiwan where he taught in an elementary school and studied Chinese Ch’uan Fa, which included Taku, Makaitan, Rutaobai, and Ubo. Given this diverse martial arts background, the Japanese government soon recognized Toyama’s prowess, and awarded him the right to promote to any rank in any style of Okinawan karate. An official gave Toyama the title of master instructor.

In early 1930 he returned to Japan and on March 20, 1930, he opened his first dojo in Tokyo. He named his dojo Shu Do Kan meaning „the hall for the study of the karate way.” Toyama taught what he had learnt from Itosu and the Ch’uan Fa and did not claim to have originated a new style of karate. In 1946, Toyama founded the All Japan Karate-Do Federation (AJKF) with the intention of unifying the various forms of karate of Japan and Okinawa under one governing organization.

The individuals listed below are Shudokan pupils of Toyama. The translated partial list includes the karate-do shihan and hanshi title license and high degree rank (fifth dan to eighth dan). The symbol indicates persons and organizations that did not train directly with Toyama, but were confirmed as members with the responsibilities of the shihan title and high degree rank. The symbol indicate partial or missing translations.

Tatsuo Shimabuku (島袋 龍夫)

Tatsuo Shimabuku (島袋 龍夫)

Tatsuo Shimabuku (September 19, 1908 – May 30, 1975) was the founder of Isshin-ryū („Whole Heart Style”, „One Heart Way”) karate.

Tatsuo Shimabuku was born in Kyan [Chan] village, Okinawa, on September 19, 1908. He was first born of ten children born into a farming family. By the age of 12, he had a strong desire to study the martial arts. He walked to the nearby village of Shuri a distance of 12 miles, to the home of his uncle, Shinko Ganiku, a fortuneteller. Shinkichi primarily learned to be a fortuneteller from his uncle, but also studied the rudiments of the karate that his uncle had learned while in China.

Eizo Shimabukuro (b.1925) is a younger brother of Tatsuo’s who also excelled in martial arts. Eizo studied under his elder brother, Tatsuo, and is said to have also studied under the same masters as Tatsuo, such as Chotoku Kyan, Choki Motobu, Chojun Miyagi, and Shinken Taira.

While the older brother went on to create his own new style of karate, Eizo quickly moved up the ranks in Shōrin-ryū (Shōbayashi).

By the time Shimabuku was a teenager, he had obtained the physical level of a person six years his senior. His physical condition was due to his karate training as well as his working on the family farm. He excelled in athletic events on the island. By the time he was 17, he was consistently winning in two of his favorite events, the javelin throw and high jump.

Around the age of 23, because of Shimabuku’s desire to further his knowledge, he began to study Shuri-te, which later became known as Shorin-ryu (Shao-lin Style) under Chotoku Kyan in the village of Kadena. He began his training with Kyan in 1932. Kyan taught Shimabuku at his home. Kyan also taught at the Okinawa Prefectural Agricultural School. Within a short time, he became one of Kyan’s best students and, under Kyan’s instruction, learned the katas: Seisan, Naihanchi, Wansu, Chinto and Kusanku along with the weapons kata Tokumine-no-kun and basic Sai. He also began his study of „Ki” or Chinkuchi in Okinawan dialect) for which Kyan was most noted. Shimabuku studied with Kyan until 1936. He always considered Kyan his first formal Sensei and was very loyal to him.

Shimabuku had always been fascinated by Naha-te (Goju Ryu) and sought out Chojun Miyagi, the founder of Goju Ryu. Miyagi’s teacher was Higaonna Kanryo (also called Higashionna) who brought a derivative of Kenpo kin gai is the name of this system. pangai noon is the forerunner of Uechi-ryu) from China to Okinawa. Eventually this became Naha-te. From Miyagi, Tatsuo learned the kata Seiunchin („Seize-Control-Fight”) and Sanchin („Three-Fights/Conflicts”).

After his studies with Miyagi, in 1938, Shimabuku sought out another famous Shorin-Ryu instructor, Choki Motobu. Choki Motobu was probably the most colorful of all of Shimabuku’s instructors. Motobu had many teachers for short periods of time, including some notables such as Anko Itosu (Shuri-te) and Kosaku Matsumora (Tomari-te). Motobu was known for getting into street fights often in his youth to promote the effectiveness of karate. Shimabuku studied with Motobu for approximately one year.

Shimabuku opened his first dojo in 1946 after the war in the village of Konbu, near Tengan village.

Coming from a farming family, Shimabuku had always been poor, yet he was very innovative and opportunistic. He had a natural talent in adapting things to work for him. As a young man, he discovered a way to bind tile to the roofs of homes in Chun Village without using mud, which had been the traditional way. Prior to World War II, he saw an opportunity and started a small business. Purchasing several horses and carts, he received a contract to help in the construction of Japanese airfield in Kadena. He was doing quite well until the Allied invasion of Okinawa began. During one of the bombing raids by Allied forces, his business was destroyed.

Shimabuku continued to study and develop his skills in both styles, but he was not satisfied that either style held the completeness he felt a style should have. His interest in ancient weapons (Kobudo) continued to grow and he sought out the most renowned weapons instructors on the island for at the time he only knew bo (staff) kata, Tokumine no Kun and basic sai techniques he learned from Chotoku Kyan. In a short time, he became a master in such weapons as the Bo and Sai. (During the late 1950s and early 1960s, he continued his study of Kobudo with one of Moden Yabiku’s top students, Shinken Taira. This training took place in Shimabuku’s dojo in Agena.) He learned Hama Higa no Tuifa, Shishi no Kun, Chatan Yara no Sai, and Urashi Bo. Shimabuku created Kyan Chotoku sai and Kusanku sai using sai techniques he learned from Chotoku Kyan. To honor Chotoku Kyan, he named his first sai kata after him.

It was during the late 1940s that Shimabuku began experimenting with different basic techniques and Kata from the Shorin-Ryu and Goju-Ryu systems as well as Kobudo. He comes to experimenting with his own ideas. He called the style he was teaching Chan-migwha-te after Chotoku Kyan nickname Chan-migwa. Kyan’s nickname was “Chan-migwa”, meaning “small-eyed-Chan.” „Chan” in the Okinawa dialect “Uchinaguchi” is “Kyan.In Uchinaguchi “mi means “eye.” The suffix “Gwa” or “Guwa” mean’s “small.” So Chan-migwa means “Small eye Chan (Kyan).” Chan migwa-te was the style taught until he renamed his style „Isshin-ryū” on January 15, 1956.

By the early 1950s Shimabuku was refining his karate teaching combining what he felt was the best of the Shorin-Ryu and Goju-Ryu styles, the weapons forms he had studied, and incorporating his own techniques. As his experimentation continued, his adaptation of techniques and katas were not widely publicized. He consulted with several of the masters on Okinawa concerning his wish to develop a new style. Because he was highly respected as a karate Master, he received their blessings. (These would later be rescinded due to the many radical changes made in traditional Okinawan karate.)

One night in 1955, Mr. Shimabuku fell asleep and dreamed of a goddess riding a dragon. The goddess was Kannon the Buddhist Goddess of mercy and compassion.

Three Stars appeared symbolizing the three styles Isshin-ryu derived from, Goju-Ryu, Shorin-Ryu, and Kobudo. The stars can also represent the Physical, Mental, and Spiritual strength needed for Isshin-ryu. The gray evening sky symbolized serenity and implies that karate is to be used only for self-defense.

The next morning when Shimabuku awoke, he felt that his dream had been a divine revelation. He met with his top student, Eiko Kaneshi, and told him of his dream and his desire to break away from Okinawan tradition and start a new style of karate. The day was January 15, 1956. Upon announcing his decision to start a new style, many of his Okinawan students left, including his brother Eizo.

The new system was not initially given a name, and in fact, went through 2 name modifications before Isshin-ryū was finally adopted. However, the official start of Isshinryu karate is January 15, 1956. The Isshin-ryū Megami was drawn from Shimabuku’s description by Shosu Nakamine, Eiko Kaneshi’s uncle, and was chosen to be the symbol for Isshin-ryū karate.

During his karate career, Shimabuku changed to his name “Tatsuo,” meaning “Dragon Man.” Whenever asked about this change, Shimabuku would reply that “Tatsuo” was his professional karate name. He also was given the nickname, “Sunsu”, by the mayor of Kyan (Chan) Village. Sunsu was a name of a dance that was created by Shimabuku’s grandfather.

Gigō Funakoshi (船越義豪)

Gigō Funakoshi (船越義豪)

Gigō Funakoshi (Funakoshi Gigō, Funakoshi Yoshitaka in Japanese) (1906—1945) was the third son of Gichin Funakoshi(the founder of Shōtōkan karate) and is widely credited with developing the modern karate Shotokan style.

Gigo Funakoshi was born in Okinawa and diagnosed with tuberculosis at the age of seven. He was sickly as a child and began the formal study of karate-do at the age of twelve as a means to improve his health. In the early years, Gichin Funakoshi often took Gigo with him to his trainings with Anko Azato and Anko Itosu. Gigo moved from Okinawa to Tokyo with his father when he was 17, and later became a radiographer of the Section of Physical and Medical Consultation of the Ministry of Education.

When his father’s Shihan (senior assistant instructor) Takeshi Shimoda passed away Gigo assumed his position within the Shotokan organization teaching in various universities. Gichin Funakoshi transformed karate from a purely self-defense fighting technique to a philosophical martial Dō (way of life), or gendai budo, but his son Gigō began to develop a karate technique that definitively separated Japanese karate-do from the local Okinawan arts.

Between 1936 and 1945, Gigo gave it a completely different and powerful Japanese flavor based on his study of modern kendo (the way of the japanese sword) under sensei Hakudo Nakayama. Gigo’s work on Karate development was primarily assisted by Shigeru Egami and Genshin Hironishi

Through his teaching position and understanding of Japanese martial arts, Gigō became the technical creator of modern shotokan karate. In 1946 the book Karate Do Nyumon by Gigo and Gichin Funakoshi was released. Gigo had written the technical part, whereas his father Gichin wrote the preamble and historical parts.

While the ancient arts of To-de and shuri-te emphasized the use and development of the upper body, open hand attacks, short distances, joint locks, basic grappling, pressure point striking and use of the front kick and variations of it, Gigō developed long distance striking techniques using the low stances found in kendo kata. Gigo developed higher kicks including mawashi geri (round kick), yoko geri kekomi (thrusting side kick), yoko geri keage (snap side kick), fumikiri (cutting side kick directed to soft targets), ura mawashi geri (quarter rotation front-round kick—though some credit Kase-sensei with the creation of this technique), ura mawashi geri (360 degrees turning round kick) and ushiro geri kekomi (thrusting back kick). Yoshitaka was especially known for his deep stances and kicking techniques, and he introduced kiba dachi (side stance), yoko geri (side kick), and mai geri (front kick) forms to the Shotokan style. All these techniques became part of the already large arsenal brought from the ancient Okinawan styles.

Gigo’s kicking techniques were performed with a much higher knee-lift than in previous styles, and the use of the hips was emphasized. Other technical developments included the turning of the torso to a half-facing position (hanmi) when blocking, and thrusting the rear leg and hips when performing the techniques. These adaptations allowed the delivery of a penetrating attack with the whole body through correct body alignment. Gigo also promoted free sparring.

Gigō’s kumite (fighting) style was to strike hard and fast, using low stances and long attacks, chained techniques and foot sweeps. Integration of these changes into the Shotokan style immediately separated Shotokan from Okinawan karate. Gigo also emphasized the use of oi tsuki (lunge punch) and gyaku tsuki (reverse lunge punch). The training sessions in his dojo were exhausting, and during these, Gigo expected his students to give twice as much energy as they would put into a real confrontation. He expected this over-training would prepare them for an actual combat situation, should it arise.

The difficult living conditions of World War II weakened Gigo, but he continued training. He died of tuberculosis at the age of 39 on 24 November 1945, in Tokyo, Japan.

Tsuyoshi Chitose

Tsuyoshi Chitose

The history of Chito-ryu karate begins with our founder, Tsuyoshi Chitose (1898-1984). He was born in the Kumochi area of Naha City on the island of Okinawa on October 18, 1898. It was the 29th year of the Meiji era in Japan. Here on this small island, known as the cradle of karate-do, Tsuyoshi Chitose grew up and spent his early formative years.

His original birth name was Chinen (Gochoku) Masuo. His father Chinen (Masuo) Chiyoyu, married into his wife’s last name, and was not a practitioner of karate. Chitose Sensei changed his name to Tsuyoshi Chitose for personal reasons after he moved to Tokyo in 1922 to attend medical college.

In tracing the history of Chito-ryu, we must also look into the historical influences that shaped Chitose Sensei’s martial arts experiences and impacted our art of today. The old karate and martial arts teachers were responsible for influencing future generations of karate practitioners with the ideas they developed during their lifetimes. Some of these ideas were passed to Doctor Chitose and aided him in his creation of Chito-ryu.

Chitose Sensei’s mother’s grandfather was a very famous karate master. His name was Sokon (Bushi) Matsumura (1797-1889). Matsumura Sensei was considered one of the great karate (Tode) figures of the nineteenth century. Matsumura Sensei started his karate training when he was thirteen years old. His father, Sofuku Matsumura, took him to see a seventy eight year old karate teacher named Tode (Karate) Sakugawa. Sakugawa Sensei (1733-1815) was born in Akata Cho, a small section of the city of Shuri, Okinawa. When Sakugawa was a young man he had been a student of Takahara Peichin (1683 – 1760). He had also studied for six years (1756 to 1762) with a Chinese military envoy (Kusanku). It is from this part of our history that we get the kata – Seisan, Niseishi, Sochin, Sakugawa No Kon Sho, and Kusanku. Years later Bushi Matsumura had an opportunity to train with a Chinese trader named Chinto. When Chinto returned to China, Matsumura Sensei developed a kata from the many movements he had learned and named it Chinto in his teacher’s honor. This kata is presently required for Sho-Dan (1st degree black belt) by the U. S. Chito-ryu Karate Federation.

In 1886 Jigoro Kano, the founder of Judo, established the kyu/dan belt system. In 1907 he designed the Judo uniform from which the karate uniform is taken, except that the karate jacket is much lighter in weight.

In 1886 Jigoro Kano, the founder of Judo, established the kyu/dan belt system. In 1907 he designed the Judo uniform from which the karate uniform is taken, except that the karate jacket is much lighter in weight.

In 1895 the Japanese government created the Dai Nippon Butokukai to oversee the martial arts, and provided two titles – Hanshi, the highest award, and Kyoshi. In 1934 the Dai Nippon Butokukai created a third title, Renshi, which was below that of Kyoshi. On April 12, 1924 Gichin Funakoshi became the first karate teacher to award black belts when he adopted Jigoro Kano’s practice of awarding this rank to advanced students. Experiments in kumite training were initiated between 1924 and 1927 at Tokyo University. By 1927 these students were practicing tournament type sparring. All these elements played major roles in the development of Chito-ryu.

Chitose Sensei started his Tode (karate) training when he was seven years old (1905). His first teacher was a sixty year old man by the name of Unchu (Nigaki) Kamade Arakaki (1840-1920). Arakaki Sensei taught the young Chitose his first kata – Seisan.The method of teaching karate in those days was to teach kata. The practice of basics and kumite, which is common today, was unknown. In the olden days many karate teachers refused to have or claim a style. They said that they just taught karate (Tode), style or ryu was never an issue. For years the young Chitose practiced the one kata, Seisan. Only after he reached the age of fourteen did Arakaki Sensei teach him his second kata.

When young Tsuyoshi Chitose entered high school he had the opportunity of further training with Sensei Anko Itosu (1832-1916). Itosu was born in Yamagawa Village, Shuri, and was a student of Sokon Matsumura. It is believed Itosu Sensei developed the Chinese corkscrew punch into its present form, and also originated the Pinan (Heian) kata. In April, 1901, Itosu Sensei introduced karate training to the Shuri Jinjo Elementary School as part of the physical fitness training. During 1905 he introduced karate training into the Prefectural Teachers Training College. Three years later, under his guidance, karate training was introduced into all Okinawan schools.

One of Chitose Sensei’s young school friends was Shoshin Nagamine, who would one day found the Matsubayashi Shorin-ryu style of karate, and become president of the Okinawan Karate Federation. One of their school teachers, later recognized as the greatest karate master of the twentieth century, was Gichin Funakoshi (1868-1957), the father of modern karate and founder of Shotokan. Another of Chitose Sensei’s classmates was Funakoshi Sensei’s son, Gikko (Yoshitaka) Funakoshi.

Other kata taught to Doctor Chitose were: Shihohai, Niseishi and Sanchin from Arakaki Sensei; Chinto, Bassai, and Kusanku from Chotoku Kiyan Sensei (1870-1945); Ryusan from Chiyomu Hanagusuku; and Rohai from Kauryo Higashionna (1851-1915). Also training there at this time with Higashionna Sensei were Mr. Chojun (Miyagi) Miyagusuku (1888-1953) founder of Goju Ryu karate and Mr. Kenwa Mabuni (1888-1953) the founder of Shito-ryu karate.

From 1922-1932 Chitose Sensei went to college, practiced karate in his spare time,and assisted his old school teacher Gichin Funakoshi with his college karate classes. In 1931 Chitose Sensei assisted a new student at the Takushoku University karate club. His name was Masatoshi Nakayama (1913-1986), who would one day be the head instructor of the Japan Karate Association (Shotokan). During this time Dr. Chitose also established his medical practice. During the war he served in the Army Medical Corps and spent some time in China. While serving in a small village in China Dr. Chitose befriended the local citizens. As a result of his assistance to the local population, he came into contact and was trained by an old Chinese Gung-fu teacher.

In 1936 O-Sensei was present at a meeting of Okinawan karate authorities in Naha, Okinawa. This was the meeting in which the translation „Empty Hand Way” was actually adopted for Karate-do in place of the original todejutsu or „Chinese Hand Method”.

In March 1946 Doctor Chitose opened a small karate dojo Yoseikan (training hall) in Machi, Kirkuchi-Gun, Kumamoto Prefecture (presently called Kirkuchi City). He later held an Okinawan Kobudo Taikai (Tournament) at the Kubukiza in Kumamoto City to help raise relief funds for Okinawa. In 1948, O-Sensei organized the All Japan Karate-do Federation (Zen Nihon Karate-do Renmei) along with Gichin Funakoshi, Mabuni, Higa Seko, and Toyama Kanken and served as president for some time. It was around this time that O-Sensei named his style Chito-ryu. Although it may seem obvious that „Chito” is a derivation of Chitose, this in fact is not the case. „Chi” is derived from „thousand” and „to” is from the Chinese „Tang”, hence the translation of Chito-ryu is „The thousand year old Chinese (Tang dynasty) way”, signifying the ultimate origin of Karate as being from China during the Tang era roughly one thousand years ago.

At this time the practice of most martial arts (kendo, judo and others associated with the nation of Japan) had been forbidden by the allied powers under the command of General Douglas MacArthur. Karate was considered an Okinawan art form and was not subject to the close scrutiny given to Kendo and Judo. Nevertheless, Doctor Chitose and other martial arts teachers were very secretive in the teaching of their respective arts. Much of the martial arts training was camouflaged as physical fitness exercises and dances. In most instances the occupying powers just looked the other way. This was the existing political climate when Masami Tsuruoka received his first degree black belt in karate from Doctor Tsuyoshi Chitose. The year was 1949.

Masatoshi Nakayama (中山 正敏) Father of modern sports karate

Masatoshi Nakayama (中山 正敏) Father of modern sports karate

Nakayama Masatoshi April 13, 1913 – April 15, 1987) was an internationally-renowned Japanese master of Shotokan karate. He helped establish the Japan Karate Association (JKA) in 1949, and wrote many textbooks on karate, which served to popularize his martial art. For almost 40 years, until his death in 1987, Nakayama worked to spread Shotokan karate around the world. He was the first master in Shotokan history to attain the rank of 9th dan while alive, and was posthumously awarded the rank of 10th danNakayama was born on April 13, 1913, in the Yamaguchi prefecture of Japan. He was descended from the Sanada clan, who were known as kenjutsu instructors, from the Nagano region. Nakayama’s grandfather was Naomichi Nakayama, a surgeon in Tokyo, who had also been the last of the family to teach kenjutsu. Nakayama’s father was Naomichi Nakayama, an army physician and a judoka (practitioner of judo). His father was assigned to Taipei, so Nakayama spent some of his formative years there. Apart from his academic studies, he participated in kendo, skiing, swimming, tennis, and track running

Nakayama entered Takushoku University in 1932 to study Chinese language, and began learning karate under Gichin Funakoshi and his son Yoshitaka (also known as Gigō). He had originally planned to train in kendo, but misread the schedule and arrived at karate training instead—and, interested by what he saw, ended up joining that martial art group. Nakayama graduated from Takushoku University in 1937. That same year, he travelled to China as an interpreter during the Japanese occupation of China. By the time World War II began, Nakayama had attained the rank of 2nd dan. Nakayama returned to Japan in May 1946, after the war

In May 1949, Nakayama, Isao Obata, and other colleagues helped establish the Japan Karate Association (JKA). Funakoshi was the formal head of the organization, with Nakayama appointed as Chief Instructor. By 1951, Nakayama had been promoted to 3rd dan, and he held the rank of 5th dan by 1955. In 1956, working with Teruyuki Okazaki, he restructured the Shotokan karate training program to follow both traditional karate and methods developed in modern sports sciences. In 1961, Nakayama was promoted to 8th dan—a remarkable progression, in part made possible by the consensus-based system of higher dan promotion in Japan at the time, according to Pat Zalewski. Nakayama established kata (patterns) and kumite (sparring) as tournament disciplines. Students of the large JKA dojo (training halls) subsequently achieved an unmatched series of tournament successes in the 1950s and 1960s.

Nakayama is widely known for having worked to spread Shotokan karate throughout the world. Together with Funakoshi and other senior instructors, he formed the JKA instructor trainee program. Many of this program’s graduates were sent throughout the world to form new Shotokan subgroups and increase membership. Nakayama also held positions in the Physical Education department of Takushoku University, beginning in 1952, and eventually becoming head of that department. He also headed the ski team at the university.