ISTORIA OKINAWA KARATE

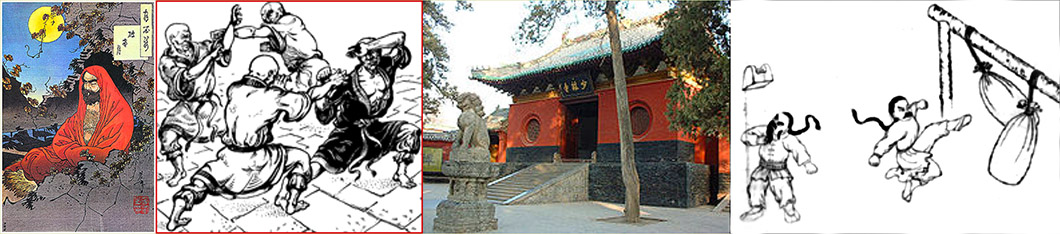

According to ancient Okinawan legend, Karate had its beginnings in India with a Buddhist monk named Daruma. Tradition says that Daruma traveled across the Himalayan Mountains from India to the Shaolin Temple in Honan Province of China. There he began teaching the other monks his philosophies of physical and mental conditioning. Legend has it that his teachings included exercises for maintaining physical strength and self defense.This same monk known as Bodhidharma in India and as Ta Mo in China, is credited with founding the school of Buddhist philosophy known as „Ch´an” in China and as „Zen” in Japan.The Okinawans believe that the art known as Karate today came from those original teachings of Daruma through an Okinawan who visited or lived for some time in China at the Shaolin Temple. Whether or not this is true, it is obvious that there are similarities in the Okinawan art of Karate and the language and martial arts of China.Further, we must assume that the Karate of Okinawa developed from trial and error of fighting experiences into a different and unique martial art.

Karate (空手)is a martial art developed in the in what is now Okinawa, Japan. It was developed from indigenous fighting methods called te (手, literally „hand”; Tii in Okinawan) and Chinese kenpō.Karate is a striking art using punching, kicking, knee and elbow strikes, and open-handed techniques such as knife-hands. Grappling, locks, restraints, throws, and vital point strikes are taught in some styles.A karate practitioner is called a karateka (空手家).

Karate was developed in the Ryukyu Kingdom prior to its 19th-century annexation by Japan. It was brought to the Japanese mainland in the early 20th century during a time of cultural exchanges between the Japanese and the Ryukyuans. In 1922 the Japanese Ministry of Education invited Gichin Funakoshi to Tokyo to give a karate demonstration. In 1924 Keio University established the first university karate club in Japan and by 1932, major Japanese universities had karate clubs.In this era of escalating Japanese militarism,the name was changed from 唐手 („Chinese hand”) to 空手 („empty hand”) – both of which are pronounced karate – to indicate that the Japanese wished to develop the combat form in Japanese style.After the Second World War, Okinawa became an important United States military site and karate became popular among servicemen stationed there.

The martial arts movies of the 1960s and 1970s served to greatly increase its popularity and the word karate began to be used in a generic way to refer to all striking-based Oriental martial arts. Karate schools began appearing across the world, catering to those with casual interest as well as those seeking a deeper study of the art.

Shigeru Egami, Chief Instructor of Shotokan Dojo, opined „that the majority of followers of karate in overseas countries pursue karate only for its fighting techniques…Movies and television…depict karate as a mysterious way of fighting capable of causing death or injury with a single blow…the mass media present a pseudo art far from the real thing.” Shoshin Nagamine said „Karate may be considered as the conflict within oneself or as a life-long marathon which can be won only through self-discipline, hard training and one’s own creative efforts.”

For many practitioners, karate is a deeply philosophical practice. Karate-do teaches ethical principles and can have spiritual significance to its adherents. Gichin Funakoshi („Father of Modern Karate”) titled his autobiography Karate-Do: My Way of Life in recognition of the transforming nature of karate study. Today karate is practiced for self-perfection, for cultural reasons, for self-defense and as a sport. In 2005, in the 117th IOC (International Olympic Committee) voting, karate did not receive the necessary two thirds majority vote to become an Olympic sport.Web Japan (sponsored by the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs) claims there are 50 million karate practitioners worldwide.

Karate began as a common fighting system known as te (Okinawan: ti) among the Pechin class of the Ryukyuans. After trade relationships were established with the Ming dynasty of China by King Satto of Chūzan in 1372, some forms of Chinese martial arts were introduced to the Ryukyu Islands by the visitors from China, particularly Fujian Province. A large group of Chinese families moved to Okinawa around 1392 for the purpose of cultural exchange, where they established the community of Kumemura and shared their knowledge of a wide variety of Chinese arts and sciences, including the Chinese martial arts. The political centralization of Okinawa by King Shō Hashi in 1429 and the ‘Policy of Banning Weapons,’ enforced in Okinawa after the invasion of the Shimazu clan in 1609, are also factors that furthered the development of unarmed combat techniques in Okinawa.

There were few formal styles of te, but rather many practitioners with their own methods. One surviving example is the Motobu-ryū school passed down from the Motobu family by Seikichi Uehara.Early styles of karate are often generalized as Shuri-te, Naha-te, and Tomari-te, named after the three cities from which they emerged.Each area and its teachers had particular kata, techniques, and principles that distinguished their local version of te from the others.

Members of the Okinawan upper classes were sent to China regularly to study various political and practical disciplines. The incorporation of empty-handed Chinese Kung Fu into Okinawan martial arts occurred partly because of these exchanges and partly because of growing legal restrictions on the use of weaponry. Traditional karate kata bear a strong resemblance to the forms found in Fujian martial arts such as Fujian White Crane, Five Ancestors, and Gangrou-quan (Hard Soft Fist; pronounced „Gōjūken” in Japanese).Further influence came from Southeast Asia—particularly Sumatra, Java, and Melaka.Many Okinawan weapons such as the sai, tonfa, and nunchaku may have originated in and around Southeast Asia.

Sakukawa Kanga (1782–1838) had studied pugilism and staff (bo) fighting in China (according to one legend, under the guidance of Kosokun, originator of kusanku kata). In 1806 he started teaching a fighting art in the city of Shuri that he called „Tudi Sakukawa,” which meant „Sakukawa of China Hand.” This was the first known recorded reference to the art of „Tudi,” written as 唐手. Around the 1820s Sakukawa’s most significant student Matsumura Sōkon (1809–1899) taught a synthesis of te (Shuri-te and Tomari-te) and Shaolin (Chinese 少林) styles. Matsumura’s style would later become the Shōrin-ryū style. Matsumura taught his art to Itosu Ankō (1831–1915) among others. Itosu adapted two forms he had learned from Matsumara. These are kusanku and chiang nan. He created the ping’an forms („heian” or „pinan” in Japanese) which are simplified kata for beginning students. In 1901 Itosu helped to get karate introduced into Okinawa’s public schools. These forms were taught to children at the elementary school level. Itosu’s influence in karate is broad. The forms he created are common across nearly all styles of karate. His students became some of the most well known karate masters, including Gichin Funakoshi, Kenwa Mabuni, and Motobu Chōki. Itosu is sometimes referred to as „the Grandfather of Modern Karate.

In 1881 Higaonna Kanryō returned from China after years of instruction with Ryu Ryu Ko and founded what would become Naha-te. One of his students was the founder of Gojū-ryū, Chōjun Miyagi. Chōjun Miyagi taught such well-known karateka as Seko Higa (who also trained with Higaonna), Meitoku Yagi, Miyazato Ei’ichi, and Seikichi Toguchi, and for a very brief time near the end of his life, An’ichi Miyagi (a teacher claimed by Morio Higaonna).

Ankō Itosu

Grandfather of Modern Karate

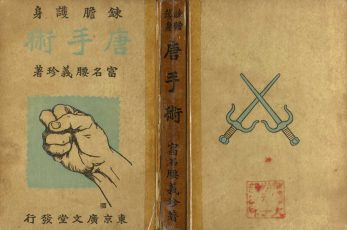

Karate Jutsu

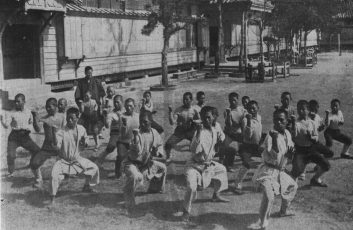

Okinaw Karate Dojo

In addition to the three early te styles of karate a fourth Okinawan influence is that of Kanbun Uechi (1877–1948). At the age of 20 he went to Fuzhou in Fujian Province, China, to escape Japanese military conscription. While there he studied under Shushiwa. He was a leading figure of Chinese Nanpa Shorin-ken at that time.He later developed his own style of Uechi-ryū karate based on the Sanchin, Seisan, and Sanseiryu kata that he had studied in China.

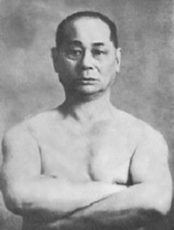

Higaonna Kanryo

founder of Naha-te

Gichin Funakosi Father of Modern Karate founder of Shotokan-ryu

Gichin Funakoshi, founder of Shotokan karate, is generally credited with having introduced and popularized karate on the main islands of Japan. In addition many Okinawans were actively teaching, and are thus also responsible for the development of karate on the main islands. Funakoshi was a student of both Asato Ankō and Itosu Ankō (who had worked to introduce karate to the Okinawa Prefectural School System in 1902). During this time period, prominent teachers who also influenced the spread of karate in Japan included Kenwa Mabuni, Chōjun Miyagi, Motobu Chōki, Kanken Tōyama, and Kanbun Uechi. This was a turbulent period in the history of the region. It includes Japan’s annexation of the Okinawan island group in 1872, the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895), the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905), the annexation of Korea, and the rise of Japanese militarism (1905–1945).Japan was invading China at the time, and Funakoshi knew that the art of Tang/China hand would not be accepted; thus the change of the art’s name to „way of the empty hand.

„The dō suffix implies that karatedō is a path to self knowledge, not just a study of the technical aspects of fighting. Like most martial arts practiced in Japan, karate made its transition from -jutsu to -dō around the beginning of the 20th century. The „dō” in „karate-dō” sets it apart from karate-jutsu, as aikido is distinguished from aikijutsu, judo from jujutsu, kendo from kenjutsu and iaido from iaijutsu. Funakoshi changed the names of many kata and the name of the art itself (at least on mainland Japan), doing so to get karate accepted by the Japanese budō organization Dai Nippon Butoku Kai. Funakoshi also gave Japanese names to many of the kata. The five pinan forms became known as heian, the three naihanchi forms became known as tekki, seisan as hangetsu, Chintō as gankaku, wanshu as empi, and so on. These were mostly political changes, rather than changes to the content of the forms, although Funakoshi did introduce some such changes. Funakoshi had trained in two of the popular branches of Okinawan karate of the time, Shorin-ryū and Shōrei-ryū. In Japan he was influenced by kendo, incorporating some ideas about distancing and timing into his style.

He always referred to what he taught as simply karate, but in 1936 he built a dojo in Tokyo and the style he left behind is usually called Shotokan after this dojo. The modernization and systemization of karate in Japan also included the adoption of the white uniform that consisted of the kimono and the dogi or keikogi—mostly called just karategi—and colored belt ranks. Both of these innovations were originated and popularized by Jigoro Kano, the founder of judo and one of the men Funakoshi consulted in his efforts to modernize karate.

Chojun Miyagi

founder of Goju-ryu

Motobu Choki

founder of Motobu-ryu

Kenwa Mabuni

founder of Shito-ryu

Kanbun Uechi

founder of Uechi-ryu

Hironori Otsuka

founder of Wado-ryu

In 1922, Hironori Ohtsuka attended the Tokyo Sports Festival, where he saw Funakoshi’s karate. Ohtsuka was so impressed with this that he visited Funakoshi many times during his stay. Funakoshi was, in turn, impressed by Ohtsuka’s enthusiasm and determination to understand karate, and agreed to teach him. In the following years, Ohtsuka set up a medical practice dealing with martial arts injuries. His prowess in martial arts led him to become the Chief Instructor of Shindō Yōshin-ryū jujutsu at the age of 30, and an assistant instructor in Funakoshi’s dojo.

By 1929, Ohtsuka was registered as a member of the Japan Martial Arts Federation. Okinawan karate at this time was only concerned with kata. Ohtsuka thought that the full spirit of budō, which concentrates on defence and attack, was missing, and that kata techniques did not work in realistic fighting situations. He experimented with other, more combative styles such as judo, kendo, and aikido. He blended the practical and useful elements of Okinawan karate with traditional Japanese martial arts techniques from jujitsu and kendo, which led to the birth of kumite, or free fighting, in karate.

Ohtsuka thought that there was a need for this more dynamic type of karate to be taught, and he decided to leave Funakoshi to concentrate on developing his own style of karate: Wadō-ryū. In 1934, Wadō-ryū karate was officially recognized as an independent style of karate. This recognition meant a departure for Ohtsuka from his medical practice and the fulfilment of a life’s ambition—to become a full-time martial artist.

Ohtsuka’s personalized style of Karate was officially registered in 1938 after he was awarded the rank of Renshi-go. He presented a demonstration of Wadō-ryū karate for the Japan Martial Arts Federation. They were so impressed with his style and commitment that they acknowledged him as a high-ranking instructor. The next year the Japan Martial Arts Federation asked all the different styles to register their names; Ohtsuka registered the name Wadō-ryū. In 1944, Ohtsuka was appointed Japan’s Chief Karate Instructor.

Karate can be practiced as an art (budo), as a sport, as a combat sport, or as self defense training. Traditional karate places emphasis on self development (budō).Modern Japanese style training emphasizes the psychological elements incorporated into a proper kokoro (attitude) such as perseverance, fearlessness, virtue, and leadership skills. Sport karate places emphasis on exercise and competition. Weapons (Kobudo) is important training activity in some styles.Karate training is commonly divided into Kihon (basics or fundamentals), Kata (forms), and Kumite (sparring).In the bushidō tradition dojo kun is a set of guidelines for karateka to follow. These guidelines apply both in the dojo (training hall) and in everyday lifeOkinawan karate uses supplementary training known as hojo undo. This utilizes simple equipment made of wood and stone. The makiwara is a striking post. The nigiri game is a large jar used for developing grip strength. These supplementary exercises are designed to increase strength, stamina, speed, and muscle coordination.Sport Karate emphasises aerobic exercise, anaerobic exercise, power, agility, flexibility, and stress management.All practices vary depending upon the school and the teacher.Gichin Funakoshi said, „There are no contests in karate.”In pre–World War II Okinawa, kumite was not part of karate training.Shigeru Egami relates that, in 1940, some karateka were ousted from their dojo because they adopted sparring after having learned it in Tokyo.

In 1924 Gichin Funakoshi, founder of Shotokan Karate, adopted the Dan system from judo founder Jigoro Kano using a rank scheme with a limited set of belt colors. Other Okinawan teachers also adopted this practice. In the Kyū/Dan system the beginner grades start with a higher numbered kyū (e.g., 10th Kyū or Jukyū) and progress toward a lower numbered kyū. The Dan progression continues from 1st Dan (Shodan, or ‘beginning dan’) to the higher dan grades. Kyū-grade karateka are referred to as „color belt” or mudansha („ones without dan/rank”). Dan-grade karateka are referred to as yudansha (holders of dan/rank). Yudansha typically wear a black belt. Requirements of rank differ among styles, organizations, and schools. Kyū ranks stress stance, balance, and coordination. Speed and power are added at higher grades.

Minimum age and time in rank are factors affecting promotion. Testing consists of demonstration of techniques before a panel of examiners. This will vary by school, but testing may include everything learned at that point, or just new information. The demonstration is an application for new rank (shinsa) and may include kata, bunkai, self-defense, routines, tameshiwari (breaking), and/or kumite (sparring). Black belt testing may also include a written examination.

Masters of karate in Tokyo (1930)

Kanken Toyama, Hironori Ohtsuka, Takeshi Shimoda, Gichin Funakoshi,

Motobu Choki, Kenwa Mabuni, Genwa Nakasone and Shinken Taira

(from left to right)

Commemorating the establishment of basic kata of karate do (1937)

Chotoku Kyan, Kentsu Yabu, Como Hanashiro,Chojun Miyagi (front from left)

Shinpan Shiroma (Sinpan Gusukuma), Choryo Maeshiro, Chosin Chibana,

Genwa Nakasone (back from left)

The Twent Guiding Principles of Karate

Master Funakoshi explained his philosophy of karate, in greater detail, in the twenty principles called the nijyu kun.Throughout his life, Master Funakoshi emphasized the importance of spiritual over physical matters, and he believed that it was essential for the karate student to understand why—not only for training, but in the way the student lives every moment of his life. In his book, Karate-do Kyohan, Master Funakoshi discussed both the positive and negative aspects of karate, warning us that karate-do can be misused if misunderstood. He felt that those who wanted to learn karate should understand what karate really is—what its purpose, its ultimate objective, should be. Only then could a karate student understand how to use karate techniques and skills properly.

When we get to the very essence of karate, to the ultimate purpose of training—that’s what it’s all about: Improving ourselves as people. If we all try to make ourselves the best human beings we can be, we will make the world a better place. We will help bring peace. That was Master Funakoshi’s ultimate goal—to make peace in the world by helping people develop themselves, as individual human beings, through karate-do. It is every instructor’s duty to help realize this goal. And it is the responsibility of every student as well. When you repeat the dojo kun after class, and you say it from your heart, you acknowledge that responsibility.

The principles of the dojo kun are simple and very basic. They are simply stated, and so require little explanation. Here we will give a brief explanation of each principle, keeping it as simple as the principle itself.

The message behind each of the nijyu kun is often more difficult to understand, however, and so we devote more time to explaining them. As you will see—and as I said before—the basic principles of the dojo kun are reflected in the principles of the nijyu kun. The dojo kun is the foundation of the nijyu kun.

As we explain the meaning of the nijyu kun, you will see the basic, simple ideas of the dojo kun everywhere. And again, the last four parts of the dojo kun reflect the very first, the most important principle of all: Seek perfection of character.

Always remember: The most important thing you can do as a true student of karate is to seek perfection of character. The dojo kun and the nijyu kun explain both how and what it means to do so, not only in karate training, but in the broader terms of life, generally.

Of course there is no substitute for training. Training is the process by which we learn to improve ourselves as people. Training is our path to the spiritual growth Master Funakoshi encouraged us to attain. But it is important to understand why we train. Karate, more than anything else, is a spiritual endeavor. It is a way to develop a person as an individual. If a karate student does not understand this basic objective, then he or she is not really practicing karate.

Helping people become the best human beings they can be is what karate is all about.